The combination of cover and author name recognition are usually unbeatable, which is why, despite my issues while reading my first work by the author last year (review here), I requested this ARC.

Beware: racism; domestic abuse; alcoholism; stillbirth; chronic illness (sickle cell disease); gambling addiction.

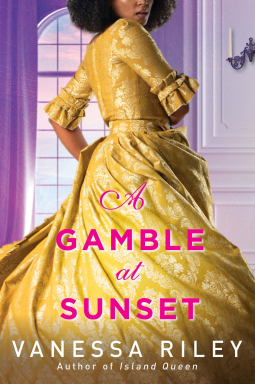

A Gamble At Sunset, by Vanessa Riley

Ostensibly, the protagonists of this book are Georgina Wilcox, daughter of a Black coal merchant, and Mark Sebastian, youngest son of the influential and very racist Duke of Prahmn. She, already an outcast due to the color of her skin, her late father’s profession and some complicated family history, and he, the spare-to-the-spare and a perennial disappointment to his father, must work together to assuage the scandal stemming from being caught in compromising circumstances, before their reputations are permanently damaged.

However, as this novel is the beginning of a series that follows a battle of wills between the Duke of Torrance and the widowed Lady Hampton, eldest of the four Wilcox sisters, there is a lot of page space devoted to both their past history–because of course there’s history there–and their current corrosive enmity.

The publisher’s blurb sets the story up thus:

When a duke discovers the woman he loves was tricked into marrying another, the master chess player makes the now-widowed Viscountess the highest-stakes wager of his life in a last-ditch effort to win her affection: he will find husbands for her two sisters—or depart forever…

Georgina Wilcox, a wallflower with hidden musical talents, is furious when her reclusive older sister—the recently widowed Viscountess—refuses sorely needed help from the Duke of Torrance, the only gentleman who has shown kindness to the bereft Wilcox sisters. Georgina decides to get back at her sister and shock the Viscountess by kissing the first willing stranger she meets in the enchanting gardens of Anya House. Unfortunately, her sister is not the sole witness. A group of reporters and the ton’s leading gossips catch Georgina in a passionate embrace with a reticent composer, Lord Mark Sebastian.

The third son of an influential marquis, the tongue-tied Mark is determined to keep the scandal from ruining Georgina’s reputation and his own prospects of winning the celebrated Harlbert’s Prize for music. Under the guise of private voice lessons, the two embark on a daring gamble to fool the ton into believing that their feigned courtship is honorable while bolstering Georgina’s singing genius to captivate potential suitors. Sexist cartoons, family rivalries, and an upcoming ball test the fake couple’s resolve. Will their sudden fiery collaboration—and growing attraction—prove there’s nothing false about a first kiss and scandalously irresistible temptation?

The novel is narrated in first person, past tense, mostly by Mark and Georgina, although there are a couple of key chapters from the Duke of Torrance’s point of view. In fact, most of the history between the duke, the late Lord Hampton, and Katherine, the latter’s widow, is set before the reader in chapter 3 (more on this below).

Once upon a time, the Wilcox coal business had provided a comfortable living and helped establish the family’s respectability; the Wilcox sisters received educations comparable to those of gentlewomen, and the family lived in comfort and security. Then the eldest got pregnant out of wedlock, and though there was a stillbirth, the damage to all their reputations was done. A few years later, she married the white son of a viscount, partly in hopes that his connections would help them regain their lost social standing; instead, his unbridled gambling cost them most everything, and his recent death has left the Wilcox sisters without any protection from the white society that has resented a Black family’s prosperity for decades.

The only redeeming act in the late unlamented Lord Hampton’s life was to send for his erstwhile closest friend from his deathbed, knowing that once the duke learned the truth, he would protect the Wilcoxes. After all, Torrance has always loved Katherine, and would never let her resentment deter him from keeping her and her sisters safe.

For the next year, the duke does just that, quietly working behind the scenes to thwart the machinations of white aristocrats such as the Marquis of Prahmn–a man with whom Torrance himself has an account to settle–who want to take them uppity Black women who dared to marry up, down all the way to the gutter. Over this time, Torrance earns the younger sisters’ trust and affection, even though the widowed Lady Hampton still despises him and resents his help.

When Georgina, the second eldest of the Wilcox sisters, impulsively kisses a stranger during a somewhat public event at his house, the duke’s careful strategy seems in danger of falling apart. A bold plan to deceive society and defang the gossip is set in place: the two people involved will fake a temporary engagement while working to make Georgina a socially desirable wife over the next few weeks. Once she has other viable options, she will publicly break the engagement. (More on this in a bit.)

In his late twenties at this point, Lord Mark Sebastian has no money of his own and is entirely dependent on her mother’s connections to get commissions as a music tutor or helping wealthy families design music rooms for their estates or town houses; he aspires to make a name for himself as a composer, thus finally becoming financially independent from the father who despises him.

While he is clearly quite talented, Mark often struggles to translate the music in his head to paper notations; for several years he has failed to finish a piece of music in time to enter it into a prestigious contest where, should he win, the purse and the public recognition would go a long way to securing his future. And then there’s the paralysing shyness that often leaves him mute in social situations–especially but not only when interacting with attractive women.

For years, Mark has been infatuated, almost obsessed, with the portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle (historical figure, extant painting), and he’s captivated by Georgina’s resemblance to her; this fascination eventually helps him break through his shyness and social anxiety enough to talk to her.

Georgina Wilcox is 25; given that the family can no longer afford servants, she has learned to bake (and presumably also to cook, though this is not mentioned at any point in the novel). In fact, we are told often that her biscuits (cookies for U.S. readers) are absolutely amazing, and there’s a little subplot involving Mark never being in time to snag even one to taste.

For quite a bit of the book, Georgina’s behavior is that of a much younger person. Whenever she is stressed, she runs–literally. It is during one of these flights after an argument with Katherine that the infamous kissing happens, in fact.

While the Wilcox sisters love each other dearly, there are several undercurrents of resentment in their relationships. Katherine’s marriage to a feckless gambler has cost her sisters their dowries, which has essentially condemned all to spinsterhood, never mind that it also means that they now live in genteel poverty; the fact that he was white and titled has also provoked enough racist backlash as to endanger what little of their father’s coal business survived the late Viscount’s gambling, is insult added to injury.

Georgina is impulsive and has zero interest to help her sister run what’s left of the coal business–she runs, twirls, bakes, hums, and occasionally plays their later mother’s pianoforte (which somehow didn’t get sold to pay gambling debts). Scarlet, all of twenty, is so interested in science that she often dresses like a man to attend lectures at the Royal Society–which means that she frequently disappears from the house for hours at a time, and apparently Katherine never notices this. Lydia, just five, has a recurring illness–the same affliction that killed Mrs Wilcox. (We learn through the author’s note at the end that sickle cell anemia runs in the family, which historically affected mostly Black people of African descent–including some white-passing individuals.)

And then there are the secrets the eldest Wilcox continues to keep from her sisters.

The novel deals with a lot of heavy issues; the racism and politics of the early 1800s are showcased both individually in the person of the Marquis of Prahmn, and in the unutterably horrid cartoons about Georgina and Mark that soon appear in the popular rags (the author names the historical cartoonists of the time that inspired the ones described in the book).

Mark is clearly written to be somewhere in the autism spectrum; he struggled with speech as a child, and is still often not comfortable holding conversations, occasionally going involuntarily non-verbal in stressful circumstances. He gets lost in his own thoughts often, which leads him to miss entire conversations–this is how he finds himself in the duke’s garden in time to kiss Georgina, and how he fails to realize the depth of his mother’s racism for so long.

Speaking of the marchioness, she is portrayed as a fully dimensional person, for all that she has little page space. While she holds the same racist views as most white people of her time–especially those whose families had owned slaves until fairly recently–and often acts out of a degree of self-interest when it comes to encouraging Mark to distance himself from “the Blackamoor woman”, she’s also shown to love her son deeply, and her suffering under the emotionally abusive marquis is treated with compassion and sympathy.

There is so much focus on the conflict between Katherine and the duke, and on the conflicts between Georgina and Katherine, between Mark and his family, and between Mark and his friend Livingston, that there’s not enough space to develop the relationship between the putative leads.

In fact, I was never fully convinced of the emotional connection between Mark and Georgina, though I appreciated that her reluctance to go from a short fake engagement to a true relationship with him is based on realistic concerns. After all, she already lived through the societal response to her sister’s interracial marriage to a member of the aristocracy, never mind that they are both essentially penniless.

And while it’s is clear, even without the note at the end, that the author did a lot of research on the period, from scientific discoveries to the social and political climate of the time, and while the feeling of the period–misogyny, racism, the power differential between the classes, etc–is very much there, I felt that the way most of the historical figures and discoveries were introduced into the narrative by the characters was forced, and that often jolted me out of the story.

The author’s choice to reveal so much of the history between Torrance and Katherine made several conversations between Katherine and Georgina redundant, killing the narrative momentum. In fact, there was quite a lot of repetition of known facts, and not in conversations with different characters, but between the same two people. Katherine and Georgina fight half a dozen times over the former’s reason to reject the duke’s offers of help; Mark and Livingston discuss the facts behind the latter’s almost hysterical rejection of marriage for every man he likes–which includes Mark and the duke–something like four different times.

And while it’s true that actual human interaction involves a lot of this kind of going around in circles, fiction has to make sense where reality rarely does.

Which brings me back to the whole fake engagement, and later the famous wager between the duke and Katherine, over marrying off the younger Wilcox sisters. The former would make some sense if the plan was to have the happy couple spend time in public, attending social functions, having the duke introduce them to some of his own acquaintances, in order to showcase whatever is supposed to make Georgina a desirable wife, rather than a “grasping, opportunistic Blackamoor bent on seducing a naïve white aristocrat” (as Katherine has been perceived by white society since her own marriage).

Instead, the plan is to have Georgina “exhibit” (the word the author uses for “perform”) at the ball: she will sing a hymn while Mark plays, and this will, somehow, elicit enough obvious interest from other single men in attendance that she will publicly end their “secret” fake engagement, then…something something, all is well for them both.

As Mark and Georgina have their own push-pull over this, what with him already head over heels within minutes of their meeting, and her thinking to herself around the half point of the book that she loves him–never mind they’ve barely spent any time in each other’s company—the duke and Katherine have the fight to end all fights, and the famous wager comes into being.

Which, as it happens, makes even less sense than the fake engagement.

There were other issues; having the man of all work, whose English, we are told, “wasn’t the best”, making references to Greek mythology, with perfect grammar, in the same scene felt off. Stressing that Mr Thom is their only servant, who they often can’t pay for weeks at a time, but never referencing essential and time-consuming housework chores, such as cooking, laundry, or hauling water up for the oft-referenced baths young Lydia doesn’t want to take, made the Wilcoxes’ poverty less real.

Also, and perhaps this is a case of the Mandela effect, the familiarity with which the servants treat their employers in this book was jarring; I can understand it from Mr Thom, as the Wilcox fortune rose and fell within his own service to the family, and even somewhat from the duke’s butler due to that nobleman’s personal history, but it felt out of place from the Marquis of Prahmn’s butler, as that aristocrat is clearly very class conscious and intolerant.

Finally, the same editing issues I noted in my review of Murder in Westminster are present in this ARC: several instances where words are clearly missing, or the wrong one is used (face for gaze, plane for plain, and so on); the Marquis of Prahmn being referred to as a duke at least once; slight jumps in action, so that characters are in one place or position in one sentence, and somewhere else in the next; etc.

Further, in the scene where the duke talks with the soon-to-die Viscount Hampton, the latter essentially says, “this is how I destroyed your life, and also the full details of my perfidy are in that letter over there”. After he promptly dies, there’s no mention of the letter ever again–even though the scene is narrated in first person by the duke himself. (I will note here that perhaps some of the details of the letter are important later on in the series, and therefore the author didn’t want to include its full text in this novel; I maintain that there are other ways to keep the letter’s contents from the reader.)

So while the novel had an intriguing premise and promising characters, and while I appreciate the author building a nineteenth century Britain that is as diverse in every way as the historical one was, I struggled with too many aspects of the story, and in the end wasn’t convinced that Georgina and Mark love each other.

A Gamble at Sunset therefore gets a 7.00 out of 10

Good heavens, I’m exhausted just reading this. From your review the whole thing feels very “way too much going on” and the romance suffers for it.

So much happening! And so little focus on the two people whose romance the book is purportedly about.

I feel like I have the complaint with so much happening it disappears the romance so much lately. Why is the romance not the focus in a romance genre book??

I’ve read a couple Riley books and since I nerd out to her history, I’ll generally enjoy them but if I’m rating them on romance,

It’s a problem when the worldbuilding (historic background in this case), crowds out the romance plot, but here it was worse because it was the other romantic relationship that stole whatever room there was for romance after all the history.