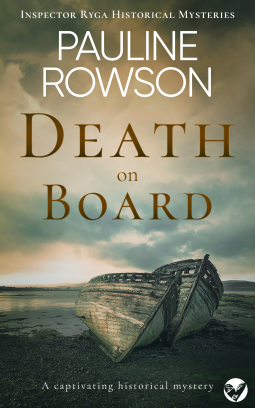

Look at that cover. Of course I had to check out the blurb, and from there to requesting an ARC it was but a very short step.

Beware: phonetic spelling to indicate accents; PTSD, copaganda; miscarriages; death of an infant; depression; mental health issues; suicide on page; sexual coercion/rape; xenophobia; antisemitism.

Death on Board, by Pauline Rowson

This is the fifth entry in a series of historical police procedurals following the investigations of Inspector Alun Ryga, a one time member of the Merchant Navy and later POW in a German concentration camp, turned police detective after his release and demobilization, through the good services of a fellow prisoner.

The publisher’s blurb sets up the story thus:

1951.

Inspector Alun Ryga surveys the wreckage of the elegant Harley Street drawing room.It’s the home of retired dermatologist Sir Bernard Crompton, who’s currently sailing his new yacht down the British coast from Scotland — or so he was . . .

Sir Bernard is found dead on board his boat off the coast of Cornwall.

The doctor declares he died of natural causes. But why was he wearing a dinner suit with five rocks in his pocket?

Ryga heads to Cornwall to investigate, but the case takes a deadly turn when another body is found in a nearby cove with a gunshot wound to the face. The victim is also wearing a dinner suit with rocks in his pocket . . .

The story takes place over the course of a week in early May, most of it along a small stretch of the Cornwall coastline, in several small harbors and villages, and all of the narrative is from Ryga’s point of view; we spend a fair amount of time exclusively in his head.

Per force, the characterization of the other people in the story is limited to both his interactions with them, and his conclusions about what he learns from those; for most of the book, the reader is privy to Ryga’s every thought and conclusion, and it’s not until the last few chapters that the author withholds some of these; the final climactic revelations thus feel more than a bit Deus Ex Machina.

Shortly after Ryga and a local cop, Detective Sergeant Pascoe, start the investigation of Sir Bernard Crompton’s death, another body is found in a small cover nearby; luckily, this second victim is soon identified as Ralph Ackland, a civil servant with many connections to the area, who resided in London and had had no reason to visit the area since late the previous year.

Ackland, as it turns out, had been despised by virtually everyone who had dealt with him–his late wive’s sister, who lives nearby; the local police sergeant’s wife, whose late father, a boss at the local tin mine, had been subjected to Ackland’s abuse; the current captain at the same mine, who ditto; the county geologist, same; and the owner of the mine, who had spent several years at a POW camp under Japanese control in Singapore, until the end of the war in the Pacific. All of them, one after the other, tell Ryga that the man was a swine who deserved to die, and that they hope his killer will never be caught.

The police in London soon discover that Ackland’s residence has been ransacked in the same manner as Sir Bernard’s, and then the pressure is on to explain the presence of the two victims in the area, as well as the nature of their connection; despite what the local chief constable would like to believe, it would be virtually impossible for them both to be dressed in formal clothes and each with five pieces of the same rock in their pockets, both found dead within hours and in the same general area, if they hadn’t had a connection well beyond a casual acquaintance.

The sense of place and time is truly excellent, and entirely due to the cadence of the narrative and the dialogue; in a few cases, the author uses phonetic spelling to indicate a character’s accent, but generally it’s more down to the phrasing used.

“Sergeant Marrack has a constable who assists him. He lives in lodgings. Not that they have any trouble here. The miners are chapel.” (Sergeant Pascoe to Ryga, about the local cop, chapter 3)

As I mentioned earlier, Ryga had been imprisoned in a German concentration camp for four years; though his PTSD has gotten better since his return to England, in large part because his work for the police has given him something else to focus on for the vast majority of his waking hours, it’s still very close to the surface.

“Ryga was glad they had reached their destination before Pascoe could ask him about his war. He didn’t like to talk about it. Not only because there were things that he’d rather not recall but also because he saw no point in going over it. There was also the fact that when some people learned he’d been a prisoner of war, they were insensitive and stupid enough to say he’s had it easy.” (Chapter 5)

Over the course of the book, events and characters from the previous novels make repeated appearances in Ryga’s internal dialogue; from Eva Paisley, a photographer and Ryga’s apparent love interest, to Detective Superintended George Simmonds, Ryga’s sponsor and former superior in the police force. Our protagonist spends a lot of time musing over his feelings, to the point of becoming somewhat maudlin a time or two.

“He had to stop thinking in stereotypes, Ryga silently scolded himself. He’s always prided himself on keeping an open mind but it was getting decidedly soggy on this investigation” (Chapter 10)

Upon meeting Jory Logan, the mine owner, Ryga is overwhelmed both by marrow-deep sympathy, and by a resurgence of the horrors of captivity. He’s well aware that Logan’s ordeal was likely orders of magnitude harder than his, as the man bears visible physical and psychological scars, and devoutly hopes he’s not the murderer, as “he has suffered enough”.

“You cling on to the life you had before; it’s the one thing that helps to keep you going–the dreams, the wishes, the thoughts that one day it will end and you’ll be back to where you were. But when you return, the world you left behind has changed and so have you.” (Ryga to Logan, on being a POW, chapter 11)

The book is very readable, mostly because of the narrative style, which is reminiscent of other writers of the Golden Age of mystery; I cannot say I’m now as fond of Ryga as I am of Poirot or Miss Marple, however. There is a lot of plodding police work, literally walking to and fro different places, often in the rain, and while there are conversations, there’s also a lot of repetition of what another character just said, and even more moody thinking, accompanies by the occasional cup of tea or pint of bitter.

Then, all of a sudden, Ryga makes some wild reasoning leaps that connect several of the witnesses-cum-suspects and the victims, which is followed by the final contrived revelations to nail both the motive and the mechanics of the crimes.

And while the villains paid, the universe wasn’t quite righted; I did not find the ending satisfying.

Still, if plodding police work described in minute detail is your jam, this is not a bad way to spend a few hours.

Death on Board gets a 7.50 out of 10.

If plodding police work described in minute detail… OMG Az, your brain is a thing of beauty.

Look, I read the whole thing more or less in one sitting, and I wasn’t even that into it–who am I to judge what others enjoy?